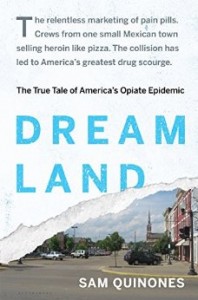

Sam Quinones has written a compelling, profoundly depressing exposé about how the twin tidal waves of prescription opiates and Mexican brown heroin have devastated much of suburban, small town and rural America, Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic. If you’re a grant writer or involved in any way with human services delivery, buy and read it now.

The “Dreamland” of the title nominally refers to the long-closed Dreamland Swimming Pool in Portsmouth, OH, a small city on the banks of the Ohio River with the ironic slogan, “Where Southern Hospitality Begins.” The defunct Dreamland Pool is an apt metaphor for the hazy memories of smaller, hollowed-out communities in the heartland. The shoelace factories that once powered the Portsmouth economy, as well as the steel mills, textile and furniture factories, and coal mines, of similar communities from the Midwest through the Rust Belt to Appalachia are gone. Despite the manufacturing renaissance in the U.S., employment in the sector is never going to reach anything like its 20th century heights.

The “Dreamland” of the title nominally refers to the long-closed Dreamland Swimming Pool in Portsmouth, OH, a small city on the banks of the Ohio River with the ironic slogan, “Where Southern Hospitality Begins.” The defunct Dreamland Pool is an apt metaphor for the hazy memories of smaller, hollowed-out communities in the heartland. The shoelace factories that once powered the Portsmouth economy, as well as the steel mills, textile and furniture factories, and coal mines, of similar communities from the Midwest through the Rust Belt to Appalachia are gone. Despite the manufacturing renaissance in the U.S., employment in the sector is never going to reach anything like its 20th century heights.

In light of economic conditions, each of these places in flyover country had its own Dreamland, along with a vibrant main street, Friday night football games in the fall, and a thousand other threads that glued them together. Now, the communities have become Dreamlands or perhaps more appropriately, Nightmarelands of opiate abuse and hopelessness.

We’ve written proposals for nonprofits in Portsmouth, as well as dozens of other, similarly forlorn communities, and consequently we’re familiar with the raw data. Some sections of Quinones’s book could have been lifted verbatim from these proposals. Here’s a quote from an actual funded proposal I wrote in 2001 (only the name of the town has been changed):

In many ways, Anyville is not really unique, as it is similar to many other small, rural communities across southern Illinois. It has seen virtually no growth in recent decades, there are few local economic opportunities, the tax base is stagnant at best, and young people tend to leave in search of more opportunities following their secondary education. There are few resources: no movie theater, bowling alley, skating rink, ice cream store, etc. There is little before or after-school programming, or structured recreational activities. At night, teens cruise and park on Main Street, with its mostly vacant storefronts.

The rural story is always the same: few jobs outside of state and local government agencies, hospitals, and big box retailers; desiccated main streets with vacant buildings, party stores, and storefront churches; high schools closed and consolidated in larger towns, due to declining enrollment and stressed tax bases; few supervised youth activities; the demise of the family farm in favor of agribusiness; enormously high rates of working age adults on disability; rampant opiate addiction, with concomitant ODs; and so on.

Although I’ve been writing versions of this proposal concept for over 20 years, Dreamland explains, in a way that I hadn’t fully grasped, the interlocking societal forces that have created this Nightmare on Main Street. If I didn’t grok this reality after writing so many proposals for the Portsmouths of the nation, seemingly no one else did, until Quinones applied the skills of an investigative reporter and borne storyteller to lift the veil.

Some changes to small-town American have been widely reported: the flight of manufacturers to emerging nations (or the growing efficiency of manufacturing plants), changing energy priorities due to climate change and fracking, stagnant incomes that result in the need for two wage earners, the rise of out-of-wedlock births and single parent households, declining populations as young people move to the coasts and Sunbelt for better employment opportunities, the atrophy of churches and fraternal organizations (see Robert Putman’s 2000 book Bowling Alone), the rise of social isolation among young people, etc.

We use these threads constantly in grant writing. In the Portsmouths we write about, the Dreamland is now the Walmart or retail mall at the edge of town. Even these ersatz community gathering spots are struggling as Amazon and other online retailers proliferate. Offline retailers are increasingly concentrating on city centers and first-tier suburbs, where the money is. In much of America, there is simply no longer a real community. Keep in mind that neither Quinones or me are talking about devastated urban neighborhoods like those in Detroit or Baltimore. Rather, the ones we’re referring to are mostly white and formerly working class to upper middle class places.

In Dreamland Quinones describes significant societal changes that are mostly unreported, not discussed, and never interwoven into the story of the decline of American communities. These include:

- The change in the view of doctors over the last 30 years to see pain management as a “fifth vital sign” and a new imperative to treat chronic pain (often with opiates).

- Unscrupulous pharma companies, with Purdue Pharmaceuticals noted in particular, flooding the market with a class of powerful opiates like OxyContin and Oxycodone. Doctors were convinced to prescribe these drugs based in part on faulty research studies claiming, erroneously, that these prescription opiates were not addictive, because the patient’s underlying pain was supposed to counter addiction. Many patients figured out almost immediately that it was easy to get high and stay high with these prescription drugs.

- The rapid proliferation of “pill mills” run by avaricious doctors in forgotten places, who would prescribe literally hundreds of pills to anyone who walked or crawled in the door with $250 in cash for the “examination and diagnosis.” Interestingly, the very first pill mill in America was in Portsmouth.

- Wide distribution of “black tar heroin” by an army of mostly undocumented immigrants from the town of Xalisco, in the small Pacific coast state of Nayarit. Quinones terms these dealers “Xalisco Boys.” Hidden in plain sight among the waves of hard-working Mexican immigrants who spread throughout America to work in slaughterhouses, industrialized hog and chicken farms, field work, and construction, the Xalisco Boys act more like pizza deliver guys than traditional street corner dealers, bringing the heroin to the user by car. Black tar heroin is purer and cheaper than the powdered heroin from the Middle East found in large cities like New York. By the early 2000s, a hit of pure black tar heroin could be bought in the Portsmouths of America for $5—less than the cost of a six pack of beer. This heroin is also cheaper than prescription opiates and it did not take long for the thousands of new pill-based addicts to switch to ubiquitous heroin. The result was (and is) an avalanche of ODs, as reported in “For Small Town Cops, Opioid Scourge Hits Close to Home.”

- As reported by the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), “Drug overdose is the leading cause of accidental death in the US, with 47,055 lethal drug overdoses in 2014. Opioid addiction is driving this epidemic, with 18,893 overdose deaths related to prescription pain relievers, and 10,574 overdose deaths related to heroin in 2014.” Even though I work with these kinds of data all the time, it was quite shocking to realize after reading Dreamland than annual ODs deaths are approaching car crash deaths.

Unfortunately, Quinones runs out of gas at the end of Dreamland. After telling this remarkable story, he drags out the usual nostrums to combat the problem—community involvement, better access to treatment, more and “smarter” law enforcement, and so on. He doesn’t ask about the economic viability of places like Portsmouth: Maybe the small towns that once existed in agricultural or manufacturing economies can’t really be saved.

In addition, having written dozens of substance abuse proposals and talked candidly with many Executive Directors of large treatment providers, I know that none of the usual strategies like community involvement and “smarter” policing actually works in fighting opiate addiction. It’s a sad reality that most Oxy or heroin addicts will eventually either OD or age out of use when, as is said in all addiction treatment programs, “they get sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

It’s very much in the interest of Seliger + Associates to encourage huge new government grant programs for treatment. One of HRSA’s favorites involves medication-assisted treatment (MAT), which I wrote about at the link. There’s about $1 billion in HRSA’s FY ’17 budget for MAT and I’m sure we’ll be writing many MAT proposals for FQHCs in the coming year.

Still, it seems to me that the only real solution to the drug component of the problems afflicting small towns is a combination of heroin legalization (or decriminalization), safe needle exchanges, medically supervised places to shoot up, and lots of education and prevention. Once the market dries up, the Xalisco Boys can find other work, and the next generation of Americans will find other ways to deal with the loss of their local Dreamland.

It’s an 8-hour trip to visit my parents, and my husband and I always drive through Portsmouth.

Reading the circumstances under which it became what I’ve always known it to be saddens me.

On another note, I just discovered your lovely blog and it has become required reading for me. Thanks for all of your fascinating posts! Me gusta.