July’s “Nonprofit Blog Carnival” asks for suggestions on “How to Create a Juicy Nonprofit Blog.” I’m not sure it’s possible to write a “juicy” nonprofit blog—I can’t see how SIX SHOCKING CELEBRITY SEX TAPE SCANDALS!!!! would apply to the sector, except as Google bait and something to draw the idea of otherwise bored readers to the article.

That being said, here’s my advice:

* Tell stories. People like stories. Joel Spolsky’s Joel on Software gets zillions of visitors not because he’s a very good programmer—which he probably is—but because he imparts his lessons through real stories about software fiascos. He says in Introduction to Best Software Writing I:

See what I did here? I told a story. I’ll bet you’d rather sit through ten of those 400 word stories than have to listen to someone drone on about how “a good team leader provides inspiration by setting a positive example.”

Yeah! In “Anecdotes,” Joel says:

Heck, I practically invented the formula of “tell a funny story and then get all serious and show how this is amusing anecdote just goes to show that (one thing|the other) is a universal truth.”

Steal someone else’s stories if you have to (I just stole Joel’s, which is a pretty solid source).

There’s a reason the Bible and most other religious texts are lighter on “thou shalts” and “thou shalt nots” and heavier on parables: the parables are way more fun. More people read novels than read legal codes, even though the novels implicitly offer examples of how to live your life. People read stories more readily than they read “how-to” manuals. Taken together, this is we often tell stories about projects, clients, and so on; my post Deadlines are Everything, and How To Be Amazing is a good example of this, since it’s basically one story after another. So is Stay the Course: Don’t Change Horses (or Concepts) in the Middle of the Stream (or Proposal Writing).

Real life is just a story generating machine. Which leads me to my next point:

* Do or have done something. I get the sense—perhaps incorrect—that some nonprofit bloggers spend more time blogging than they do working in or running nonprofits. This is like describing how to play professional baseball despite having never done so. A lot of grant writing bloggers, for example, don’t show evidence of working on any actual proposals; they don’t tell stories about projects, use specific examples from RFPs, and so on. This makes me think they’re pretending to be grant writers.*

* Be an expert and genuinely know the field. A lot of blogs that are putatively about grant writing don’t appear to have much insight into the process of grant writing, the foibles involved, the difficulty of getting submissions right, and so on. As I mentioned above, the writers seldom mention projects they’ve worked on and RFPs they’ve responded to.

* Dave Winer on great blogging:

1. People talking about things they know about, not just expressing opinions about things they are not experts in (nothing wrong with that, of course).

2. Asking hard questions that powerful people might not want to be asked.

3. Saying things that few people have the courage to say.

I would amend 3. to say “Saying things that few people have the courage or knowledge to say.”

* Don’t do something that everyone else is already doing. Every blog has “eight tips for improving your submissions,” which say things like “read the RFP before you start” and “get someone else to proofread your proposal.” Paul Graham wrote an essay against the “List of N Things” approach that’s so popular in weak magazines:

The greatest weakness of the list of n things is that there’s so little room for new thought. The main point of essay writing, when done right, is the new ideas you have while doing it. A real essay, as the name implies, is dynamic: you don’t know what you’re going to write when you start. It will be about whatever you discover in the course of writing it.

The whole essay is worth reading. Sometimes a bulleted list is appropriate, but more often it’s merely easy. Sometimes the “eight tips” are obvious and sometimes they’re wrong, but they often don’t add anything unique to a discussion.

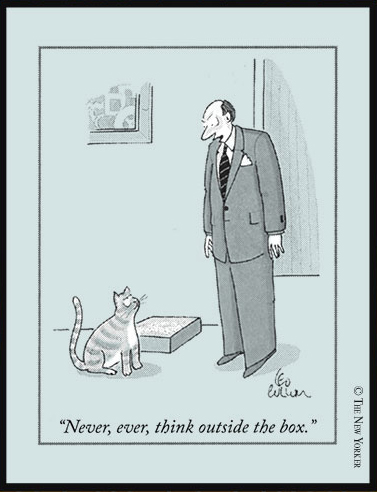

Everyone else writes posts that are 100 – 200 words long and includes pictures; we made a conscious decision to write long, detailed posts that will actually help people who are trying to write grants. Stock photo pictures don’t add anything to writing, and most of what grant writing deals with can’t be shown or expanded with pictures. So we don’t use them. Isaac, of course, insists on working in old movies, TV shows and rock ‘n’ roll lyrics, but I will not comment on these idiosyncrasies.

Writing proposals is really, really hard, and the process can’t be reduced to soundbites, which is why we write the way we write as opposed to some other way. Pictures are wonderful, but I think it better to have no pictures unless those pictures add something to the story that can’t be conveyed any other way. Generic pictures are just distractions.

As you’ve probably noticed, this post isn’t really about nonprofit blogs: it’s about how to be an interesting writer in general, regardless of the medium. Being an interesting writer has been a hard task since writing was invented, and it will probably continue to be a hard task forever, regardless of whether the medium involves paper (like books, magazines, and newspapers) or bits (like blogs) or neural channels (someday).

Finally, if you can’t take any of my suggestions but you do have a shocking celebrity sex tape, post it, and you’ll probably get 1000 times as much traffic as every other nonprofit blog combined. That’s really juicy—almost as juicy as posts that are unique and don’t merely parrot back what the author has heard elsewhere and the reader has seen before.

* I also get the feeling there are a lot of pretend grant writers out there because our clients are so often astonished that we do what we say we’re going to do. That this surprises so many people indicates to me that a lot of “grant writers” are out there who prefer to talk about grant writing rather than writing grants.